'If a person erases him or herself in order to survive, how can they find that self again?'

Posted by

Madeleine Thien

Monday 13 August 2012

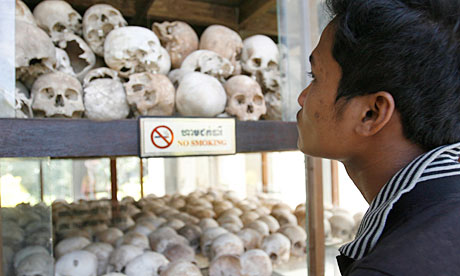

Only survive? Skulls of Khmer Rouge victims on display in Phnom Penh Photograph: Mak Remissa/EPA

When the Khmer Rouge were pushed to the edges of Cambodia

in 1979, the advancing Vietnamese army entered a capital city that

appeared to be empty. Phnom Penh, which four years earlier had been home

to two million people, was chillingly silent. The journalist Elizabeth Becker,

one of only two foreign journalists allowed into the country under the

Khmer Rouge regime, described it as a city "that had been left to rot," a

place of "eerie silence and empty streets."

- Dogs at the Perimeter

- by Madeleine Thien

-

- Buy it from the Guardian bookshop

- Tell us what you think: Star-rate and review this book

"There were," she writes, "no details in this new Cambodia."

I

first heard parts of the Khmer Rouge story when I was child. In the

early 1980s, half a million Cambodians sought refuge outside their

country. I was seven or eight at the time, and knew Cambodia only as the

country a stone's throw away from Malaysia, my father's homeland. A

great number of these refugees were children. They came without

brothers, sisters or parents and were named "separated children." On

television, they were withdrawn and quiet; for me, watching them arrive

was like being shaken awake.

In April 1975, on the day of their

victory, the Khmer Rouge began a revolution that was to be Cambodia's

Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution combined; by turning

Cambodia's back on the world - from the foreign invasions, occupations

and collaborations that had shattered their homeland - they said they

would lift their country to a better future. The Khmer Rouge demanded an

existence that combined a Buddhist renunciation of desire with the

Communist dictum that only violent revolution could cleanse a people.

Work and obedience became paramount but, even then, the most dutiful

workers were not safe. It was preferable, the Khmer Rouge held, to kill

10 innocent citizens than to let a single enemy live.

Victims

were forced to write autobiographies that, version by tortured version,

confessed to crimes they had never committed. It was safer to have no

history at all - so Cambodians enacted a silent disappearance, relying

on emptiness of expression and disavowal of feeling in order barricade

their selves, their memories, their passions and heartaches from the

world. They disappeared in the hope of one day resurfacing.

In my

30s, I began spending time in Cambodia. I found, as the months and years

passed, that I could not let the country go, and I began, despite many

doubts, to write about the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge years. There

are, I believe, eternal and harrowing questions that the Cambodian

genocide poses, and which we have never confronted. The Khmer Rouge

emptied the cities, people changed their names, let go of their

identities and effaced their selves; the world forgot a small country

that had suffered immeasurably from the interference and the wars of

larger powers.

I am almost 40 now, the novel is

finished, but my questions remain. If a person erases him or herself in

order to survive, how can they find that self again? Can survival bring

them peace, or is it only madness to remember?

One evening, I

visited a friend who had lived through the genocide. He is an older man,

in his mid-70s, and someone I have long admired. We met a year ago,

when my novel was first published. On this night, he told me that I had

written something that was a near-impossibility in Pol Pot's Cambodia: I

had allowed my character to escape in 1976, two-and-a-half years before

the regime fell. I told my friend that during the writing of this

novel, I often thought that I was writing a story of a girl who had not

survived. I was writing an existence that might have been, had such an

escape been possible.

We talked about Elizabeth Becker, about the

city eradicated of details, about the stories that never surfaced. We

talked about the meaning of escape and the complexity of survival."I think it was your character's destiny," he said finally. "It was her destiny to live her life."

Madeleine Thien discussed south-east Asian concerns with Tony Davidson at the Edinburgh International Book Festival yesterday

No comments:

Post a Comment